Photo Gallery

Stratigraphic section of Silurian of Southeastern Wisconsin. While maps provide a location in space, geologists must also locate their study sites and specimens with respect to relative geologic time. This is commonly done by identifying the geologic formation that is represented at a particular site, based on previous work in the region. In the case of Lime Kiln Park, outcrops at the study quarry are part of the Racine Formation. Work by several generations of geologists in southeastern Wisconsin has demonstrated that the Racine Formation overlies (is younger than) the Waukesha Formation and underlies (is older than) the Waubakee Formation. Previous work has also shown that the fossil content of the Racine Formation indicates a Silurian age.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

MM906 Paul Mayer exploring Grafton Silurian Reef sites. Taken during November 2013 trip led by Paul Mayer to Silurian reef sites near Grafton

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Gastropod fossil from Pre-reef deposits at Lime Kiln Park, Grafton, Wisconsin. Taken during November 2013 trip led by Paul Mayer to Silurian reef sites near Grafton, WI.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

MM906 Paul Mayer and Sharon Grant exploring Grafton Silurian Reef sites. Taken during November 2013 trip led by Paul Mayer to Silurian reef sites near Grafton, WI.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

MM906 Paul Mayer exploring Grafton Silurian Reef sites. Taken during November 2013 trip led by Paul Mayer to Silurian reef sites near Grafton, WI.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

MM906 Paul Mayer exploring Grafton Silurian Reef sites, holding up a fossil. Taken during November 2013 trip led by Paul Mayer to Silurian reef sites near Grafton, WI.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Katie Pauls and colleague collecting Silurian fossils from Lime Kiln County Park in Grafton, WI. Taken during November 2013 trip led by Paul Mayer to Silurian reef sites.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Sample bags, chisels, and sledge hammers are useful tools for sampling. When a measured section has been made, rock and fossil samples can be located according to the precise bed from which they were taken. Location according to bed is important, as it expresses the age of a sample relative to other samples from the site. Each sample is given a unique number that is marked on the specimen or sample bag and also recorded in the notes or graphic plot for the measured section. Normally a geologist will take representative samples of all of the different kinds of rocks and fossils encountered in a measured section. Actual sampling schemes vary widely. A geologist interested in ecology of reefs may sample hundreds or thousands of fossils for statistical analysis. A geologist interested in microscopic properties of sedimentary rock may take only small "hand samples" from beds.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Stratigraphic measured section of Silurian outcrop in Southeastern Wisconsin.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Measurement of a Stratigraphic Section, part 2: Photos of the entire section and individual beds are also commonly taken for additional documentation. Although measured sections can be described as written notes, they are often recorded as a graphic plot. The beds are drawn to scale, and alongside each bed, information on features such as rock type, color, sedimentary structures, and fossil content is noted. This is an example of the field data collected as a measured section at point C in the study quarry at Lime Kiln Park.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Measurement of a Stratigraphic Section, part 1: Once a geologist determines the location of a site in space and time, descriptive features of the site, such as rock type, etc., may be recorded as simple field notes. For detailed work on the geology of a site, however, the geologist records data in the form of a measured section. In a measured section, observations of the rocks are made in order from oldest to youngest beds, and the thickness of each bed (or set of beds) is measured with a tape.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Map Location: The most basic step in fieldwork is locating a site of interest on a map. In the United States, geologists and most other scientists who work in the field use topographic maps published by the U.S. Geological Survey. These maps show elevation as well as areal location. They also allow a point on the map to be expressed as latitude and longitude, universal grid coordinates, or section, township and range. This example shows the location of the study quarry at Lime Kiln Park, Grafton, on a U.S. Geological Survey map named the Cedarburg 7.5 minute quadrangle. The map location can be specified in three ways: 1) Lat/Long: 43 degrees 18 minutes 15 seconds north latitude, 87 degrees 57 minutes 30 seconds west longitude 2) Grid coordinates (Universal Transverse Mercator - UTM): Zone 16: 4794800mN 423800mE 3) Township and Range: SE1/4 of the NW1/4 of section 25, Township 10 North, Range 21 East. (Image (c) NOAA)

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

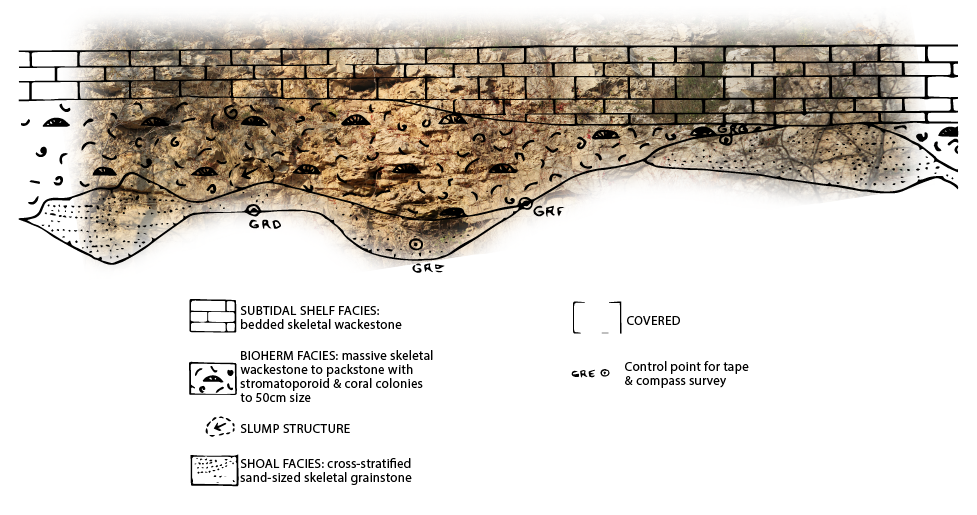

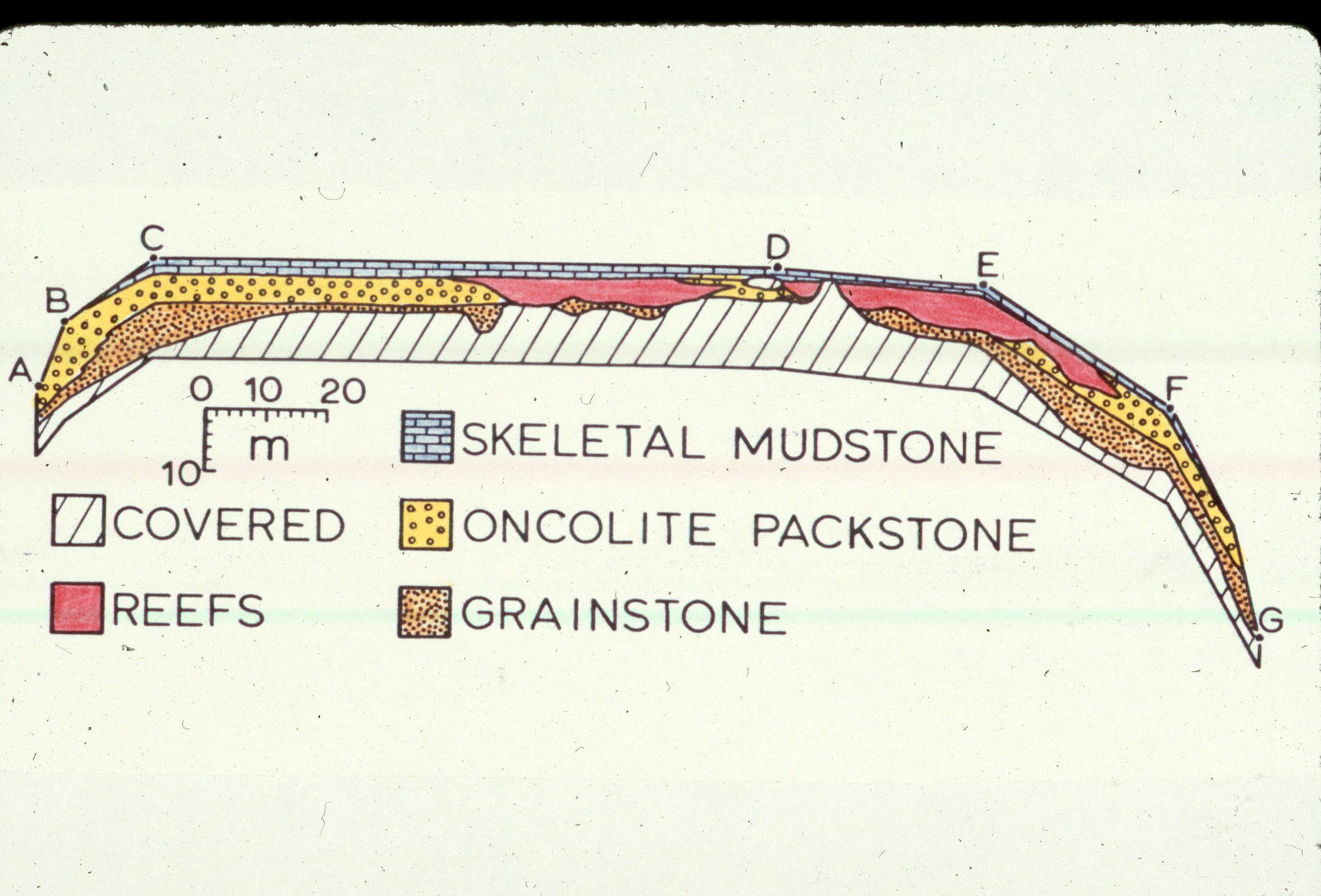

This is a cross section sketch showing reef locations and other deposits at Lime Kiln Park, Grafton, Wisconsin. When rock strata vary laterally in thickness, composition, or other features, geologists construct a cross-section to document this variation. Cross-sections may be recorded as a simple sketch, a mosaic of overlapping photos, or a series of measured sections along the face of a quarry or other outcrop. Cross-sections are particularly important in studies in ancient reefs. This example from Lime Kiln Park, constructed by tape measurements along the quarry face, shows the relation between reef and interreef deposits.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Fieldwork is one of the most important aspects of Geology and involves much more than simply going to a site and collecting rocks and fossils. No matter how beautiful or scientifically unique a specimen is, it's value is limited without a variety of accompanying data that can be gathered only in the field. Geologists who work with sedimentary rocks and fossils follow several standard procedures in their fieldwork.

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

© The Field Museum - CC BY-NC

Sites

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Hawley Road & Menomonee River. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Hartung Quarry. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Illinois, Joliet, Dellwood Park, in South Lockport. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Currie Park Quarry. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Illinois, Cook, Sagawau Canyon Nature Preserve southwest Cook County near Lemont. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Milwaukee County Stadium, Wisconsin. [LL]

-

Europe, England, Shropshire, Much Wenlock, Much Wenlock, England. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wauwatosa, Schoonmaker's Quarry. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Racine, Quarry Lake Park. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Illinois, Cook, Bridgeport (Sterns Quarry). [LL]

-

North America, USA, Wisconsin, Grafton, Lime Kiln Park. [LL]

-

North America, USA, Illinois, Cook, Thorton, Thornton Quarry, Illinois. [LL]